From January 30, 2020 through August 2, 2021, Crystal wrote a series of blogs titled Blindsided, where she shared about her experiences at the Antioch Baptist Church in Knoxville, Tennessee. Andrew Ray was, and still is, the pastor and Douglas Stauffer was his assistant. Since her time at Antioch Baptist Church, Doug Stauffer moved to Florida and became the pastor of Faith Independent Baptist Church in Niceville, Florida.

A total of 60 articles were posted. The series was never completed and no posts were deleted. Crystal had all intentions of completing the series and additional posts were planned, which is why you will see four titles without a link.

Blindsided Series

Part One: Red Flags and Rose-Colored Glasses

Part Two: Calloused Carnality and Hidden Harassment

(Sunday, June 3, 2018- Tuesday, June 5, 2018)

-

- Douglas Stauffer’s Carnal Message on Carnality- Sermon #3

- Silent No Longer

- Douglas Stauffer’s Voicemail to Matthew Olds

- Personal Response to Douglas Stauffer’s Voicemail

- Harassment from Douglas Stauffer Begins

- Private Messages Between Matthew Olds and Pastor Andrew Ray

- Afternoon Phone Calls with Pastor Andrew Ray and Douglas Stauffer

- Continuation of Messages between Matthew Olds and Pastor Andrew Ray

- Crystal Olds’ First Facebook Apology Post

- Douglas Stauffer Twists Crystal Olds’ Public Apology

- Douglas Stauffer’s Harassment Crosses Another Line

- The Olds’ House Divided

- Face-to-Face with Douglas Stauffer

- Reduced to Being the Pastor’s Cheerleader

Part Three: Navigating the Masks of Deceit

(Wednesday, June 6, 2018- Sunday, June 17, 2018)

-

- Douglas Stauffer’s Twitter Tells All (Part One)

- Douglas Stauffer’s Twitter Tells All (Part Two)

- Still Expected to Cheer from the Nursery

- Our Own Pastor- Friend or Foe?

- Our Pastor’s True Colors Begin to Show (Part One)

- Our Pastor’s True Colors Begin to Show (Part Two)

- One Finger Salute

- Douglas Stauffer’s Public Apology

- Straight from the Horse’s Mouth

- The Illusion of Pastor Andrew Ray

- Crystal Olds’ Email to Pastor Andrew Ray about Douglas Stauffer’s Harassment and Character

- Pastor Andrew Ray’s Message on “Biblical Forgiveness”

- Shredding the Evidence

Part Four: Discerning a Diotrephes: Douglas Stauffer

-

- Douglas Stauffer- A Diotrophes at Heart

- Douglas Stauffer’s Traveling Conceit

- Douglas Stauffer’s Response about the Authority of the Greek and Hebrew

- Douglas Stauffer- Pride He Can Count On

- Douglas Stauffer’s Pharisaical Comparisons

- Douglas Stauffer’s Perspective About His Pride

- A Missionary’s Dream

- Douglas Stauffer- Clouds Without Rain

- Planning on a Prayer

- Crossing I’s and Dotting T’s

- Medical Mazes (Part One)

- Medical Mazes (Part Two)

- Sent to the Wolf, Unaware

- Douglas Stauffer’s Deceitful Misleading

- Douglas Stauffer Twists the Truth

- Matthew Olds’ Email to Pastor Andrew Ray

- Douglas Stauffer’s Motives Revealed

Part Five: When Closet Skeletons Speak

-

- When Closet Skeletons Speak

- Skeleton #1: Manipulating the Broken

- Skeleton #2: The Destruction of a Young Girl

- Skeleton #3: Recordings From a Church Meeting

- Skeleton #4: A Secret Letter

- Nail in the Coffin

Part Seven: Rising Up from the Ashes

-

- Out of the Fire… With Buckets of Water

- Our Letter to the Witnesses

- Finally Speaking Out

- “What Really Happened (Part One)”

- “What Really Happened (Part Two)”

- Douglas Stauffer’s Private Message to Matthew Olds (December 2018)

- Yet Another Private Message from Douglas Stauffer (December 2018)

- Douglas Stauffer’s August 2020 Voicemail

********

Shop at our Amazon store! As an Amazon Influencer, this website earns from qualifying purchases.

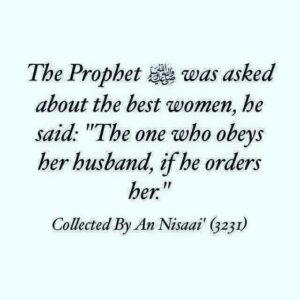

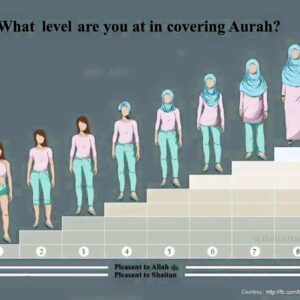

Basically the more covered your body is, the better, according to people who believe this.

Basically the more covered your body is, the better, according to people who believe this.