Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was originally published on January 3, 2016.

Back in high school, I used to love Andrée Seu Peterson’s column. I read her pieces first when our copy of World magazine arrived in the mail every week. She always made me think because she was less conservative than my homeschool textbooks, and I admired her writing style.

I haven’t read World magazine since I moved out–the subscription is expensive and I’ve had too much reading for college. Last year, though, I read about her problematic column on bisexuality in posts from Libby Anne and Samantha Field.

But in her article “Houses Taken Over” in the Nov. 14, 2015 issue, Peterson argues government oversight like food safety guidelines and background checks for child care are intrusive. She even suggests following such protocol is equivalent to Nazi Germany’s laws against Jewish people. Here we go again with Godwin’s law.

It was not long ago that the state cracked down on church homemade desserts here in Pennsylvania. The year was 2009, and as an elderly parishioner of St. Cecilia’s began unwrapping wares baked by fellow church members, a state inspector on the premises noticed that they were not store-bought and forbade their sale. It was the end of Mary Pratte’s coconut cream pie, Louise Humbert’s raisin pie, and Marge Murtha’s “farm apple” pie, as well as a tradition as old as church socials.

We Christians are a good lot, by and large. We know Romans 13 and desire to be model citizens. Would we have been sad but obedient when the 1933 “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” barred people of Jewish descent from employment in government? Would we have had searchings of heart but complied with the 1935 “Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor” that interdicted marriage between Jew and German? Would we have sighed but acquiesced in 1938, when government contracts could no longer be awarded to Jewish businesses, and in October of that year when Jews were required to have a “J” stamped on their passports?

If the local church cannot be trusted to know its people well enough to decide who is fit for nursery duty, there is nothing much to say, except that we had better get back to a New Testament model where pastors knew their flock. If bakers of coconut cream pies are notoriously dangerous people, then we have brought these statist regulations on ourselves, and more’s the pity.

The woman sitting to my right at the ESL meeting said (not disapprovingly) that from now on if a junior high event takes place at someone’s house, a person must be present who has state clearance. I hazarded at that point that it looked like government intrusion, and no one said a word, as if I had passed gas and everyone pretended I had not. As if I were the kind of person who did not care about the children.

Peterson’s article fails to differentiate between Hitler’s laws, which discriminated against Jews based off propaganda, and laws to prevent child abuse, which only restrict people convicted of a heinous crime. She also sounds defensive, as if she finds regulations burdensome and cannot understand why no one else at her church agrees with her.

American Christianity protests the removal of religious symbols from public parks, but pleads for separation of church and state when any government regulation affects church functioning. This is hypocritical. This attitude also ignores the very real problem of child abuse in both Catholic and Protestant circles.

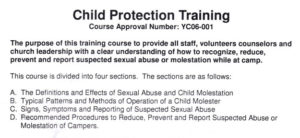

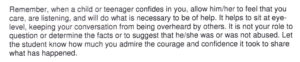

When I know that a church is following state and national guidelines, I feel safer being with that group of people. The church I recently joined requires a background check and a child protection training course for any volunteers, and I did not protest.

I actually told the nursery workers, “I’m really glad you do this.”

The 12 page booklet provides extensive definitions and examples of sex offender patterns and contrasts it with cultural stereotypes, as well as defining what is and is not appropriate protocol when working with children.

Peterson says in her column that background checks would mean less available childcare at her church.

The far-seeing ESL director realized the implications and judged that it would be prudent to scrap the baby-sitting: Fewer people would be willing to take the extra step of filling out the necessary forms. The resulting smaller pool of workers would mean that our ESL cadre would be in competition with the Women’s Bible Study ministry and the Sunday nursery ministry for manpower.

But the quiz at the end of my church’s child protection course is clear that the intent is not to prevent people from volunteering. Protecting children is the first priority.

Christians believe that Jesus said “If anyone causes one of these little ones–those who believe in me–to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.” (Matthew 18:6) If the church wants to follow this teaching, we need to be preventing child abuse through the best methods currently known.

Homeschool parents often argue that government involvement is a bad thing, and HSLDA actively encourages this. Slate magazine, the New York Times, and the Daily Beast have all reported on the lack of regulation. No accountability enables child abuse and educational neglect. This past Thanksgiving, KGOU’s article about homeschool regulation in Oklahoma was met with so much backlash from the homeschool lobby that an entire interview was withdrawn.

Societies have rules, at least in theory, so that their people can live in peace and be treated justly. Every community needs to protect the children and disadvantaged.