Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was originally published on May 24, 2017.

I got this book from a giveaway over at SpiritualAbuse.org a couple of summers ago, when I was blogging about leaving fundamentalism.

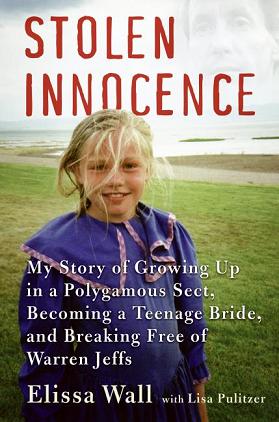

Stolen Innocence is Elissa Wall’s memoir of leaving the fundamentalist Mormon church (FLDS) as an adult. She was told to marry one of her cousins when she was only 14.

Elissa gives a good history of the FLDS in her book. She explains that the FLDS owns compounds in Utah, Texas and Arizona. Warren Jeffs has been the prophet since his father, Rulon Jeffs died. Warren Jeffs was arrested on August 28, 2006 after being on the FBI’s most wanted list and he is currently incarcerated.

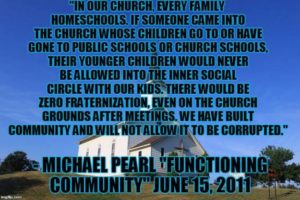

I grew up in churches that taught QuiverFull doctrine, having as many children as possible and training them up to be good little culture warriors to take back America for Christianity.

My friends and I weren’t raised in the FLDS polygamist cult, but rule-based religions tend to have similarities.

Here’s some parts that stood out to me.

Significant Quotes:

“Marriage was meant to be the highest honor an FLDS girl could receive, and I was devastated to admit to myself that I didn’t feel that way.” (p. 2)

“This is what the prophet has told me to do. I have no choice but to do it. Now is not the time to cry, I must keep sweet.” (p. 3)

The whole “keep sweet” concept is very familiar and creepy, although we used different words to describe it. My fundamentalist family and the churches we went to had a strong emphasis on being “joyful” and “uplifting” and not negative.

“Even if it hurts, you were to act happy. Even if you’re uncomfortable. That was how you conquered the evil inside of you.” (p. 399)

“At that time, the church was still known as the Work, and Dad and Audrey’s plan was to scrutinize The Work’s teachings and find its flaws, but instead found themselves swayed to its views.” (p. 11)

“Church rules forbade us form outwardly showing displeasure, so the bitterness remained just below the surface. We were taught to always put on a good face, even when things are going poorly. We were told to ‘keep sweet,’ an admonition to be compliant and pleasant no matter the circumstance. Since we couldn’t reveal our angry words and feelings, they got bottled up inside, and often there was no communication at all.” (p. 17)

Well, this is painfully familiar.

“The remote sites appealed to followers because they’d long been taught to be suspicious of all outsiders and to regard them as evil.” (p. 20)

This was basically my reaction to attending a secular university after being homeschooled in a religious household kindergarten through high school.

“…the prophet had ordered that all the books in the school library that were not priesthood-approved be burned, claiming that those who read the unworthy books would then take on the ‘evil’ spirit of their authors. The library was then restocked with books that conformed to priesthood teachings.” (p. 37)

“The fact that many in my family were smart, strong-willed, and unafraid to ask questions when things did not feel right made it hard to keep a tight hold on us. Warren didn’t like having to deal with disobedience and questions concerning the priesthood. Our religion left no room for logical reasoning and honest questioning. Warren made no attempt to understand or tolerate any of this, deeming it as absolute rebellion.” (p. 44)

“The prophet can do no wrong.” – Warren Jeffs (p. 51)

My friend Ashley’s dad said something similar about their pastor in the Apostolic Pentecostal church.

“I have literally heard my dad say that if John Burgess asked him to stand on his head for 6 hours a day, in the middle of I-25, that he would do it without hesitation.”

“‘Put it on a shelf and pray about it.’ This was Mom’s and the FLDS’s standard response to questions that had no easy answers.” (p. 55)

This was basically my mom’s response to my dad’s controlling behavior. That we had no choice but to obey and respect him.

“Unapproved pictures were removed from textbooks and anything that had to do with evolution or human anatomy was excised. In fact, anything that did not conform to our strict religious teachings and beliefs was removed from the lesson plans, and pages of books that dealt with conflicting subject matter were simply ripped out.” (p.72)

My homeschooled friends used to do this, too. Glue black construction paper over pages about halloween in craft books, staple together pages of literature textbooks that had Greek mythology.

Warren banned wearing the color red, not unlike Shyamalan’s film The Village, where red is “the bad color.”

Elissa explains that the marriage ceremony sealed wives to their husbands “for time and all eternity,” but some are only sealed for time.

When Warren Jeffs, using his father’s authority, told her to marry her cousin Allen, she prayed desperately that he would only seal them for time and not for time and eternity.

Wives could be removed from husbands that fell out of line and were deemed unworthy of the priesthood. Her mother and all her children were reassigned to their Uncle Fred.

“Fred demanded to see our entire music collection and threw out any titles he deemed ‘worldly.’” (p. 106)

Elissa writes about preparing a family meal on her own at 14 and being proud that Uncle Fred said that she would make some man very happy one day.

“I knew that this was the best compliment a girl could get. Becoming a wife was the ultimate goal and dream of all FLDS girls.” (p. 120)

I used to feel so much pride in doing housewifely or motherly things, which isn’t bad on its own, but it becomes harmful when your religion demands that your identity is to bear children and nothing else.

“Many people viewed my actions… as immature, and their attitudes made me feel like a child throwing a temper tantrum. To them, accepting the will of the prophet was simply what you were required to do. There were no questions involved, no other options.” (p. 133)

When she questions her marriage to her husband, Warren asks her if she has been praying about it. That’s also what my pastor told me when I told him that I didn’t want to transfer from my state college to Bob Jones University.

The aging prophet, Rulon Jeffs, tells her, “You follow your heart, sweetie, just follow your heart” and “God bless you and keep sweet.” She said afterwards, “The prophet told me to follow my heart and my heart is telling me not to do this.” But then Warren said, “Elissa, your heart is in the wrong place. This is what the prophet has revealed and directed you to do, and this is your mission and duty.”

Her mom tells her that the marriage can’t be that bad. (p. 142-143)

My mom used to tell me that one day I’d be married to someone and to remember that not all men are like my dad.

Allen tells Elissa after their engagement when she says she doesn’t love him that “God will change your feelings as long as you stay faithful. In time, you will feel differently.” (p.148)

Her Uncle Wendell says, “Someday thousands will flock to hear your story of faith and courage.”

When Elissa later tells the prophet that she is unhappy and her cousin (now husband) is hurting her, he tells her to ignore those feelings and just obey.

“You are doing insane things that will lead you to be unfaithful. Sometimes in our lives, we are told to do things that we don’t feel are right. Because the Lord and the prophet tell us to, then they are right. You need to put your heart and feelings in line. You need to go and repent. You are not living up to your vows. You are not being obedient and submissive to your priesthood head. And that is your problem. You need to go home and repent and give yourself mind, body, and soul to Allen because he is your priesthood head and obey him without question because he knows what’s best for you. He will be directed by the priesthood and the spirit of God to know how to handle you.” – Warren (p.189)

“I was keeping sweet just like they’d always told me to, and in the process I started to forget some of the doubts that I’d had about the FLDS as my wedding approached. For the first time in months, the questions I’d been asking myself about why God forced us to marry and broke apart families became to subside. Finally I was learning how to smile for the camera.” (p. 196)

Parents in the FLDS church are required to abandon “unworthy children.”

“What had once been a community of industrious people who lived by the motto ‘love thy neighbor as thyself’ had slowly shifted to become a society of paranoid and fearful souls. Everyone was looking over his shoulder to see what his neighbor was doing and Warren was encouraging people to report any wrongdoing.” (p. 243)

High control groups do this with their members. They encourage turning in anyone who is not considered faithful and obedient enough.

Her mom says she won’t let this happen to her sisters, but Elissa wonders if there is really anything her mom could do. I often feel this way about conversations with my mom, too.

“She sounded sincere, but I had a hard time believing that there was anything she could do to stop it from happening to Sherrie and Ally—not unless she was willing to forego her eternal salvation and leave the religion with my two little sisters.” (p. 245)

“Her staunch support of the religion and inability to extract herself from that mindset put me in a position where she couldn’t protect me. It is for this reason that I have resolved to make it my mission to help my little sisters and others like them in any way possible.” (p. 429)

Elissa remembers being told not to question authority, that rebellion would cause her to lose her faith.

“Your problem is that you are questioning Allen and the priesthood itself. And when you question the priesthood and your priesthood head, you are questioning God. … You need to be careful about what you do because you will lose your faith.” (p. 250)

“You’d be much happier if you just allow yourself to follow the prophet.”

“The work of God is a benevolent dictatorship. It is not a democracy.” (p. 285)

I was also taught theology like this.

When she meets her now husband, Lamont, a former FLDS kid who left, he tells her to make a choice in her own heart. He is probably the first person in her life who encourages her to trust herself.

Once she finally talks to a victim’s advocate in the court system, she realizes most people believe what happened to her was not okay.

“Even though I was older than most of the victims she usually interviewed, I was still very childlike. What came out of this meeting was the realization that what had happened to me was wrong in the eyes of the world.” (p. 351)

“I’d been taught to fear people like them my whole life, but in such a short time, all that had changed.” (p. 359)

“All they know about people on the outside is what they have been taught; that they are evil, and the thing that had surprised me most in my transcendent journey from the FLDS to the life I live now is that good, honest, and respectful people lived out here and are nothing like what we’d been taught they are.” (p. 421)

This is how I felt when I met people on the outside, too.

Like many other unhealthy churches, sexual abuse was hidden because the authorities feared it would make the church look bad.

“He was told that the priesthood would take care of it and was not to go to the authorities because it would cast a bad light on the people. Of course, we heard that the young man’s parents had been informed of the incident, but from all accounts nothing else was ever done.”

“Had someone done something to stop him back then, perhaps those other victims would have been spared.” (p. 361)

Elissa testified against Warren Jeffs during his trial and found freedom in it.

“I was no longer his victim, and with that realization I was liberated.” (p. 368)

“I looked like the person I felt inside, and this is a magical thing when it has been denied for so much of your life.” (p. 378)

“Somehow deep down I’d always thought he would get away with it. Now that he hadn’t, I didn’t know how to feel. All I could think of was that none of this would have happened if I hadn’t had the reminder of all my sisters to give me strength to stand up to do what I knew was right.” (p. 419)

She mentions the 2008 government raid on the Texas ranch at the end of the book.

“As hard as it has been to watch the events of Eldorado unfold, they prove that there are still so many young girls and women around the world whose faces I’ll never see and whose names I’ll never know, and that perhaps in some way my words will help them to use their strength to reclaim what is rightfully theirs—the power of choice.” (p. 431)

Elissa’s book was a quick read. She writes in a conversational tone that helps you relive her experiences with her.

The text could have been edited to be more concise and have more punch, but I also know she only had an 8th grade education because the cult prevented her from continuing school after marriage.

Overall, Stolen Innocence is compelling.

********

Shop at our Amazon store! As an Amazon Influencer, this website earns from qualifying purchases.