Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was originally published on November 9, 2014.

I cry, Father, Father, forgive me

You say, Child, I already have.

– Joy Williams, Beautiful Redemption

I pulled back on the bowstring, my arm trembling to hold it taut.

My friend Ashley gave me pointers from the other side of the archery pit.

“Pull your finger back before you release so the arrow doesn’t catch.”

“Aim a bit to the other side and higher.”

Steel slipped between my two hands, out and away through the crisp November dusk. The arrow struck the hay bale near orange spray paint.

“Hey! That one wasn’t bad!” I said, extracting the arrow from the netting.

Using a bow and arrow involves rewiring neural connections to tune hand-eye coordination. Which takes repetition. I still miss, mostly.

Living requires the same dedication. I mess up every day, missing a deadline, saying the wrong thing.

But, as my friend Elraen often says, you are not what you do.

Modern church has many sermons and worship choruses about sin and sinners. We’re told from an early age that “we have all sinned, and come short of the glory of God,” as part of the Romans Road.

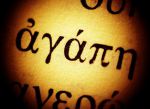

But cultural connotations are lost in language translation, because Koine Greek and Hebrew have evolved into modern forms.

In my two semesters of Koine Greek this year, I discovered the original meaning of “sin.” The word is ἁμαρτία, pronounced “hamartia” and means “to miss the mark,” specifically in archery. Basically, a mistake. Sinner is ἁμαρτωλός: a poor marksman or mistake-maker.

But our American culture has no physical reference for the word. So we’ve made it a state of being. Pretty much since the word came into the English language.

In the opening paragraphs of A Christmas Carol, Dickens uses it to describe Ebenezer Scrooge:

“Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner!”

And Shakespeare does it, although Elizabethan England lacks the rigid sanctimoniousness of Victorian society:

“Those healths will make thee and thy state

look ill, Timon. Here’s that which is too weak to

be a sinner, honest water, which ne’er left man i’ the mire”

(Apemantus, in Timon of Athens – Act 1, Scene 2)

“Well, I will be so much a sinner, to be a

double-dealer: there’s another.”

(Duke Orsino, Twelfth Night – Act 5, Scene 1)

English usage often links sinner with a “be” verb, making “sinner” a label, a title. Like an occupation. The word becomes an identifier, it sticks to us.

Guess who else liked to use “sinner” to label people? The Pharisees.

The Gospels contain 30 total references to “sinner.”

Five of them are used by the gospel writers (Matthew 9:10, Mark 2:15, Mark 2:16, Luke 7:37, Luke 15:1).

Eight times, the Pharisees point out specific people they do not approve of (twice calling Jesus a sinner). (Matthew 9:11, Mark 2:16, Luke 5:30, Luke 7:39, Luke 15:2, Luke 19:7, John 9:16, John 9:24)

Jesus uses the word 14 times, five in direct response to the Pharisee’s accusations (Matthew 9:13, Matthew 11:19, Mark 2:17, Luke 5:32, Luke 7:34), seven in talking to the disciples, often opposing some Pharisaical idea (Luke 6:32, Luke 6:33, twice in Luke 6:34, Luke 13:2, Luke 15:7, Luke 15:10), and twice when being betrayed, ironically, to the Pharisees (“into the hands of sinners,” Matthew 26:45, Mark 14:41).

Then one mention by the repentant tax collector (Luke 18:13) and twice from a healed blind man (John 9:25, John 9:31).

I get the sense that Jesus didn’t like to label people, because his conversations with the Pharisees usually go something like this:

Pharisees: “WHY ARE YOU HANGING OUT WITH /SINNERS/?”

Jesus: “Um…because I came for sinners?”

And the Pharisees don’t recognize that sometimes, they are also mark-missers.

The Gospels mention “sin” 126 times total (Matthew: 32, Mark: 21, Luke: 45, John: 28). Just the action. And those verses have new connotations for me, too.

“If your brother sins against you, go and tell him his fault, between you and him alone. If he listens to you, you have gained your brother.” (Matthew 18:15, ESV). Oh. So, if my friend misses the mark in our friendship, if I am hurt, I should tell him directly.

Humans hurt and disappoint each other every day. Sometimes missing the mark can be overcome with practice, behavior patterns can be altered.

Other times a mistake is serious or even fatal. My aim in the archery pit isn’t the sum of my identity, but a misfired arrow can wound.

Maybe that’s what Jesus’ redemption is about – he makes it so our mistakes no longer define us, so we stop attaching the name “sinner” to ourselves. The labels peel off like a used “hello my name is” sticker, and I am free.

But he saw through my labels all along.

Like ships in the night

Like ships in the night

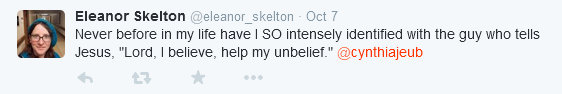

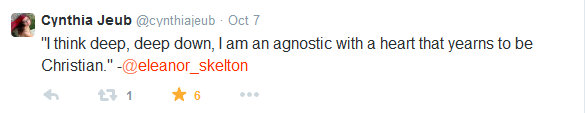

I explained it to my friend Aaron, who recently wrote a blog series on

I explained it to my friend Aaron, who recently wrote a blog series on