Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was originally published on April 16, 2015.

Some people asked us what life was like after we left when I posted the UnBoxing Project series, how we handled leaving the sects of fundamentalist Christianity we were raised in.

My friends and I went through a period of deprogramming, which is still ongoing. We’d been told what to think our whole lives, what is good and what is evil, and then we found we’d been lied to.

Cults teach the people who want to leave the group that:

1) you’re the only one questioning

2) this is somehow your fault, because everyone else is compliant and does what they’re told.

This is how they maintain control, through isolation.

My best friend in college, Cynthia Barram, found some documentaries about cults and Christian fundamentalism that demonstrated nationwide trends and helped our little group of ex-fundamentalist homeschoolers realize that we weren’t alone in deconstructing from toxic religion.

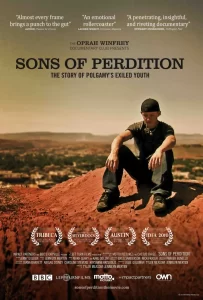

Sons of Perdition (2010)

This documentary is about the teenage boys who get kicked out and the girls and women who leave Warren Jeff’s FLDS cult on the southern Utah / Arizona border.

Although our experiences in the Independent Fundamental Baptist or United Pentecostal Churches were different than the Fundamentalist Church of Latter Day Saints since our churches didn’t practice polygamy and didn’t have a prophet, we shared many similarities with their deconstruction process. Like the ex-FLDS young adults, we grieved the loss of family members who shunned us, struggled to find a sense of purpose when we no longer felt like we had been “chosen” to fulfill a divine mission like the cult taught us, and worked through unhealthy ways of coping with these losses and found a better way to live.

The “Sons of Perdition” struggled to support themselves and enroll in school. The daughters cut their hair for the first time and put on pants. We could identify with their stories because of our own experiences in fundamentalist cults.

Daddy, I Do (2010) and Cutting Edge: The Virgin Daughters (2008 TV Show)

These documentaries are about purity culture and the father-daughter virginity ball hosted at the Broadmoor in Colorado Springs every year.

Daddy, I Do features a variety of perspectives: fraternity boys, churchgoing parents raising kids, abstinence-only program leaders, and progressive Christians like blogger Matthew Paul Turner. It addresses the problematic nature of a daughter promising her virginity to her father until marriage.

The Virgin Daughters focuses specifically on Colorado Springs and the father-daughter ball, interviewing the various families who attend and showing the pledge the fathers sign to protect their daughters’ chastity.

Both of these documentaries feature fundamentalist Christian parents who admit they actually were not virgins at marriage, but they want their children to be.

Jesus Camp (2006)

This documentary is mostly about an evangelical Pentecostal-style church camp gone wrong.

The charismatic camp director says in the opening scenes that America’s only hope for spiritual revival is through the hearts of malleable children. So she and the other leaders proceed to brainwash them and manipulate their emotions, telling the children that they are engaged in warfare for the good of the nation.

The film also shows the group of campers visiting New Life Church in Colorado Springs and meeting the pastor at the time, Ted Haggard.

Ted Haggard, who founded New Life Church in the mid 80s, was known for “waging spiritual war” in Colorado Springs and encouraging his church members to “anoint” streets and intersections with cooking oil, according to a Harpers’ Magazine article called “Soldiers of Christ” by Jeff Sharlet published in May 2005.

The neighbor family who lived across the street from my parents in Colorado Springs had attended New Life Church for years when we moved there. The husband and wife both worked at Focus on the Family while we were neighbors, and the wife often took a spray bottle of cooking oil on her walks around the neighborhood that she would use to “anoint” neighbor’s driveways if she felt that she sensed a demonic presence, in accordance with Haggard’s teachings.

Haggard resigned as senior pastor of New Life Church in the fall of 2006 after allegations surfaced that he used methamphetamine and had sex with a male escort in Denver. He and his wife left the city for several years, but he moved back to start another church in Colorado Springs in 2010, where he has been accused again of illegal drug use and inappropriate behavior with young men, according to a July 2022 article by the Colorado Springs Gazette.

Jesus Camp was a harrowing portrayal of spiritual abuse, but I needed this film to process what happened to me and my high school youth group in one of my fundamentalist churches, to realize how we had been radicalized for the culture wars.

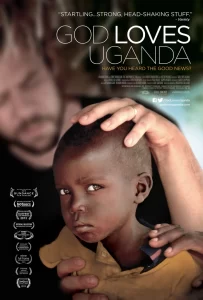

God Loves Uganda (2013)

This documentary is about non-denominational evangelical churches like the International House of Prayer (IHOP) group (which has also been called a cult) that has emerged over the last 20 years increasing missionary efforts, reacting against established denominations leaning away from traditional theology and missions.

They look at what happens on the other side, at the financial impact of this church planting and aid on the countries receiving these missionaries.

The documentary makers point out that people end up depending on the monetary support from the missionaries and churches in Western countries, and the evangelical churches sending missionaries use their influence to pass laws, like the one in Uganda that advocated the death penalty for LGBTQ people.

Basically, this film demonstrates missionary work gone bad.

Waiting for Armageddon (2009)

I’ve given up on rapture theology. The whole philosophy is based on a handful of verses and wasn’t widely accepted until television preachers in the 1960s started it during the Cold War era. If Jesus actually comes back like that, great, but if not, I’m okay with that, too.

In the film, a group of somewhat clueless Texans tromp around the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and their pastor threatens to cause an international incident by yelling that this is where Jesus will come back until security asks them to stop, reminding them that at least three different religions consider the Temple Mount to be sacred and each religion believes very different things about it.

Then they play the Star Spangled Banner while riding in a boat over the Sea of Galilee. Gotta love that American Christian exceptionalism. Lovely.

Jewish leaders who better understand the intricacies of the religious history of the area are also interviewed in the film, and it also covers the annual Tribulation Conference in Dallas, Texas.

On the lighter side, we also watched comedy movies and TV shows critiquing how we grew up.

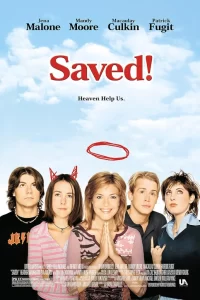

Saved! (2004)

In this movie, a high school girl decides to “save” her boyfriend from being gay by giving him her virginity. Then she gets pregnant.

And did I mention she’s in a Christian high school?

Cue goth punk chick and dude in a wheelchair (the other “outcasts”) coming to her rescue.

We laughed so much watching this film, because many of the ridiculous plot lines would actually happen in evangelical and fundamentalist subculture.

The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (2015)

In this Netflix-only series, Kimmy escapes an apocalyptic cult’s bunker after 15 years of captivity and reinvents herself and her identity in New York City.

The episode titles are hilarious from the obvious “Kimmy Goes Outside!” or “Kimmy Gets a Job!” and “Kimmy Goes on a Date!” to the more mundane, like “Kimmy Makes Waffles!”

The show received a positive review from an actual survivor of an apocalyptic cult.

I watched the first season during spring break of my last year of college and loved it, but I couldn’t watch too many episodes in one sitting because some of the comedy was too real.

When I first moved out, I was so very, very much like Kimmy, right down to her bottomless optimism. Laughing at her is like laughing at myself, which is both healing and painful.

Leaving is hard.

But for those of us who seek freedom, it’s worth it.

And we’re not alone, in this mess of deprogramming and making sense of what our lives were like and what our futures will be.

********

Shop at our Amazon store! As an Amazon Influencer, this website earns from qualifying purchases.