Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was originally published on March 8, 2015 as part of a series.

Continued from Racquel’s story.

Liz was part of our network that helped Racquel and Ashley as they left the cult environment of the First United Pentecostal Church of Colorado Springs. Here is her perspective.

Nearly two years ago, I received text messages from Eleanor about a friendship between two girls that had been recently forbidden by their religious leader.

I was asked to attempt to sneak a cheap TracFone to one of the girls at her school because I would not be recognizable to her parents, who had confiscated all her means of communication. Unfortunately, she wasn’t in class that day.

Eventually, they acquired their freedom by leaving their church behind and living with friends.

Most people assume their own community has only good intentions in mind for members. Why would we believe otherwise if an overwhelming majority of us were taught that strangers are the ones who seek to hurt us?

In reality, data suggests that most cases of violent crime and sexual assault occur between people who are at least acquainted with each other or in regular physical proximity.

In spite of statistical and factual realities, we teach our children to fear strangers. We teach them to avoid the rare anomalies but fail to teach them to look for warning signs in the mundane. This contributes to the denial in identifying abusive communities when people are a part of one.

Instead, people taught to fear the outside world might think that to leave would be worse.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt says that evil is banal. It is predictable, common, and is generally perpetuated by unremarkable people motivated by their own, typically material needs.

An intense, outward adherence to a particular ideology or manifestation of a psychological condition might be present in the situation, but neither are enough to explain why communities as a whole behave a certain way.

In other words, abusers are regular people and not the monstrous caricatures we see on TV or evil stepmothers in children’s fairy tales. There might be a few narcissists and sociopaths at the upper echelons dictating the orders, but several people who are afraid of seeking out other dissenters within the group.

With hierarchy and scale, diffusion of guilt and responsibility is inevitable. Diffusion of guilt is generally paired with resistance to collective guilt that should logically follow the diffusion.

The lower end claim to be following orders, the higher ups claim they didn’t personally do it.

It’s the same garbage that makes none guilty for abuse that many participated in. It is as if people hope that with sufficient diffusion, the amount of culpability per person is rendered insignificant. Dilution of active ingredients in homeopathic “remedies” operates this way.

Abuse as a phenomena doesn’t become significant simply because the perception of responsibility among abusers is thinly spread out because there is always someone else to blame in the eyes of the guilty such that their victims somehow become responsible for their own abuse.

What I’ve gleaned from my studies in history and politics is that there is a tendency to conceal or otherwise diminish the significance of abuses as a means of trying to protect the legitimacy and reputation of an organization such as the Catholic church, many American universities, collegiate and professional sports teams, the entertainment industry, among many other examples.

When an organization cares more about protecting its own reputation than removing abusers or helping victims, there is a reason to question the validity and value of such an institution and the complicity of people within afflicted organizations.

Even if an individual abuser recognizes the harm they cause, to reject the cultural norms is to risk being socially ostracized and possibly, their standard of living. Obedience experiments by Milgram and replicated by others show that people are generally submissive to figures of authority up to a certain point.

It is likely that people from more isolated communities would escalate punishments further when commanded by members of their community than people from the general population being instructed by a stranger because of a greater sense of obligation and desire to belong in the former.

Defection is complicated. It comes with a high price tag in both an absolute and perceived sense.

People in deliberately isolated communities are generally taught that outsiders are evil, that its their own fault for being mistreated or that victims deserve it, and that the victims aren’t being treated badly in the first place. If maltreatment is believed to be normative and benevolent it tends to make victims attempt to justify what is going on as a means of internalizing conflicting messages.

The more isolated people are, the harder it is for them to recognize their own condition and the more complex the logistics of leaving becomes.

Liz received training at a local college in her hometown so that she could teach freshmen at her high school about how to avoid and recognize dating violence, local resources for victims, and statistics regarding the frequency of rape and lack of conviction. She was also a student teacher who assisted with evening adult education courses in sexual assault escape and self-defense offered by her school to the community.

********

Shop at our Amazon store! As an Amazon Influencer, this website earns from qualifying purchases.

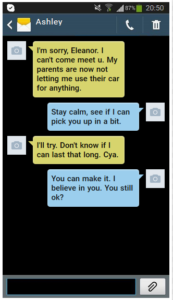

“I’m sorry, Eleanor. I can’t come meet u. My parents are now not letting me use their car for anything.”

“I’m sorry, Eleanor. I can’t come meet u. My parents are now not letting me use their car for anything.”