Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was originally published on September 22, 2014.

In this cocoon

Shedding my skin cause I’m ready to

I wanna break out

I found a way out

I don’t believe that it’s gotta be this way

The worst is the waiting

In this womb I’m suffocating

Feel your presence filling up my lungs with oxygen

I take you in

I’ve died

Rebirthing now

I wanna live for love wanna live for you and me

Breathe for the first time now

I come alive somehow

– Skillet, Rebirthing

“How does God speak to you?”

My friend Cynthia Jeub was asking me. It was January 2013. I’d only been moved out on my own for five months.

“Through his word. Through the Bible,” I answered.

“But how does God speak to you now?” she persisted.

I hesitated. Cynthia wanted to know if I believed God could speak directly to me.

“But doesn’t the Bible say that the heart is deceitful above all things and desperately wicked and who can know it?”

“That,” Cynthia Jeub said, “is the number one verse that has killed the Awana generation.”

– – – – – – – –

Rewind to July 2012.

My parents had just presented me with two options: transfer from my state school to Bob Jones University or move out without assistance. I’d stopped obeying their 7:30 pm curfews and read the Harry Potter series the previous summer. Clearly the secular university experience had corrupted the homeschool alumna.

“Eleanor, I think you should have a conversation with your heart before you decide,” my chemistry undergraduate research professor said.

I gave her a puzzled look. My mind whispered, But the heart is deceitful and desperately wicked, how could I trust it?

– – – – – – – –

I’m a frustrated, sobbing four year old.

“Stop crying. I saw how fast you turned those tears on, you can turn them off just like that,” my mom commands, snapping her fingers.

I stop. It hurts, but I shove all the tears back in where they came from. My breath is ragged from crying after a spanking.

If I’m ever going to earn my grown-up card one day, I must learn to hide what I really feel.

– – – – – – – –

Hannah Ettinger writes on her blog Wine & Marble about rediscovering her identity after being taught to avoid following your heart, and about what emotional repression did to her friend, whose parents and church victim-blamed her when she was raped.

“Jori is a very smart person, and after such strict parenting and high pressure in our church to have your emotions under control all the time, she became highly skilled at playing social roles that were expected of her. But when something traumatic happened to her, she wasn’t able to connect with her emotions to display them for an audience on command — she was too far gone into trained disassociation with her own feelings.”

Back in 2010 to about 2012, when many of my friends first met me, I couldn’t tell them how I felt. My typical response was to quote Bible verses or renowned authors on a given subject. But what did Eleanor think about this? What does Eleanor want to be when she grows up? How does she feel? No one knew.

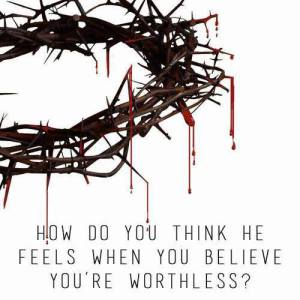

I went around everywhere being really HAPPY for everyone. Because I hoped if I could shoo away their sadness and make them whole, somehow I would defeat my own issues with self-harm and suicidal thoughts. That maybe I would be healed in healing others. But that’s not really how it works. You kind of have to confront and do battle with your own darkness before you are ever ready to help someone else with theirs.

I lived in a state of emotional hypothermia.

Another friend, Cynthia Barram, defined that for me earlier this year, when I wrestled with accepting all of my emotions, even the angry and ugly ones, as part of being human.

I explained this over chat to Cynthia Jeub in March: “when you [guys] first met me, I was in stage 3. Where *I* didn’t even know there was a problem. In stage 1, you shiver a lot. In stage 2, you’re going numb, but you’re still fighting it. Stage 3, you don’t even know you’re cold and dying.”

Cynthia Jeub responded, “Right, they went really in detail about hypothermia in my hunter’s safety class.”

“But…Eleanor. One major symptom of stage 3 hypothermia is ecstasy.”

In tomorrow’s post, I will discuss why daring to feel is worthwhile.