The following was written by former United Pentecostal Church minister Jon Eckenrod, and used with his permission. Jon held license for about twenty years and left the organization in 2007.

****************

I also want to say a word to my peers and leaders still in the ministry in the United Pentecostal Church, International. For all our efforts to “preach Jesus,” and point people to the cross, in practice we accomplished the opposite. Every time we shamed someone for not measuring up, we turned them from Jesus—not to Him. We turned them to their own lack of ability to overcome, and then to our leadership to help them become better Christians—a subject about which we were ill-equipped to offer counsel. Too many of our congregants just gave up trying and decided to either “look the part,” thereby becoming hypocrites, or leave church altogether. Of course, we attributed this to a “lack of will power” or discipline. In truth, we all know that none of us was able to live as “holy” and “pure” as we preached. Consequently, in practice, we produced an atmosphere conducive to secret sin and hypocrisy. And much to our dismay, our congregants catch on quickly. They follow the leader.

The answer for all of us lies in the grace of God, not in our efforts to become more spiritual. Pastors, it is my prayer for you and your congregations that you discover and experience the grace that I have found. What a relief to find rest, not in my ability to “pray through,” but in the arms of Jesus. – Jon Eckenrod

The proverbial elephant in the room is the issue that is plain to everyone, but about which no one wants to talk. Why don’t we like to talk about the elephants? By their nature elephants are big. To acknowledge them is to begin to deal with a problem that is uncomfortable. Usually the issue is difficult and has no easy solution. So, we ignore it, or at least we try. But, because of their size, elephants are hard to ignore. The longer we turn a blind eye to them, the more difficult they are to address. Some ‘elephants’ may start out relatively small, but over time, if not dealt with, they become enormous. And the cost of dealing with them increases with each passing day.

Dr. Joseph Umidi, one of my professors at Regent University School of Divinity, told our class that when a leader does not address elephants in the room, followers begin to “collect injustices.” In other words, they begin to take note of every mistake the leader makes. They collect them, and soon, all they can see are these injustices when they look at the leader. Dr. Umidi likened it to looking at your environment through a clear pen (one of those old-fashioned Bic pens). When the first injustice occurs, the pen appears, and it is in your line of sight (perhaps at arm’s length), but you can see everything around it clearly. As more injustices are collected, the pen moves closer to your eyes, so that it fills more of your field of vision. Soon, the pen is right next to your eyes, and you can only see everything else through the pen. This is very dangerous and very toxic. That is why it is so important for leaders to be willing to address the elephants in the room—no matter how unpleasant they are.

You don’t need a room full of people in order for elephants to appear. You can create them in your private life, which is what I did. When I saw problems and chose to ignore them, or had doubts and questions, and deferred addressing them until a later date—voila! Elephants were created. When I stopped being afraid of the truth, I began to see the elephants clearly.

Life is so very uncomfortable in a room full of elephants. In some respects, I feel like I know what an elephant stampede is like. It is overwhelming. You feel like there is nowhere to go, nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. And in truth, there isn’t. And it is very painful to endure. The elephants come straight at you, demanding to be acknowledged and dealt with. And when the stampede is over—when you have looked each elephant squarely in the eye and addressed the problems that they posed—you wonder what just happened. You try to get your bearings again. I am still in the process of doing that, but now Jesus Christ is at the center of it all. And that makes all the difference.

Life is so very uncomfortable in a room full of elephants. In some respects, I feel like I know what an elephant stampede is like. It is overwhelming. You feel like there is nowhere to go, nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. And in truth, there isn’t. And it is very painful to endure. The elephants come straight at you, demanding to be acknowledged and dealt with. And when the stampede is over—when you have looked each elephant squarely in the eye and addressed the problems that they posed—you wonder what just happened. You try to get your bearings again. I am still in the process of doing that, but now Jesus Christ is at the center of it all. And that makes all the difference.

The journey has not been easy. It has been painful at times, and my family members have been the ‘beneficiaries’ of much of that pain. But, by God’s grace, I was forced to address my elephants. I wouldn’t want it any other way (unless I could go back and stop the elephants from being created in the first place). Why was I afraid to acknowledge the truth? Why did I refuse to look objectively at the group with which I had been associated for so many years? For any one of us, the main reason is fear. Quite frankly, I was afraid that what I believed might be wrong. I was afraid of what that would mean. What would it cost me if I discovered that I was in error—that my organization was in error? What would that mean for my future, and for the future of my family? If I found that we had been wrong about our interpretation of scripture, could I stay in the organization? We were on a promising career track, and I had no desire to jeopardize that. And I certainly didn’t want to experience the ostracism that I had witnessed so many others who had left the organization experience. I didn’t want that for my family. There were too many questions with too many very troubling and painful answers. It was easier to remain ‘willfully ignorant’ than to do anything to rock the boat.

It is a sad commentary on any organization when a person must weigh whether to leave or not based on a fear of ostracism, rather than on truth and what is best for the individual or family. When this is the case, it indicates a major problem with the system. If it is fear that keeps us from looking objectively at our groups, we need to ask ourselves, “What would Jesus do?” Would Jesus cause us to be afraid to leave and go somewhere else? Would he make us fear to ask difficult questions? When we did have questions, would he shame us for doubting? Would he make us feel like we were the ones with the problem just because we questioned him? Finally, if Jesus would not make us afraid to ask the tough questions, then we need to ask another question: just what kind of people are running our organizations? Are we afraid to answer that? What an awful thing fear is. Truly, “fear hath torment,” (1 John 4:18, KJV).

It is a sad commentary on any organization when a person must weigh whether to leave or not based on a fear of ostracism, rather than on truth and what is best for the individual or family. When this is the case, it indicates a major problem with the system. If it is fear that keeps us from looking objectively at our groups, we need to ask ourselves, “What would Jesus do?” Would Jesus cause us to be afraid to leave and go somewhere else? Would he make us fear to ask difficult questions? When we did have questions, would he shame us for doubting? Would he make us feel like we were the ones with the problem just because we questioned him? Finally, if Jesus would not make us afraid to ask the tough questions, then we need to ask another question: just what kind of people are running our organizations? Are we afraid to answer that? What an awful thing fear is. Truly, “fear hath torment,” (1 John 4:18, KJV).

There were times when I would address some of these nagging doubts and questions, but it was always within the context of believing that what I was taught was true. So I had to figure out why my doubts were unfounded. Or I had to figure out a way to prove why another’s objections to my beliefs were invalid. I never addressed these things objectively. That is the way most ministers and congregants addressed these questions. We were right. We just had to figure out why others were wrong. This approach is wrong-headed, and it only serves to make our elephants grow.

My intent in writing this is to expose my own shortcomings—my own humanness, if you will. I want to demonstrate how I ignored signs that I was heading in the wrong direction. I suppressed feelings. I minimized and rationalized away warnings that should have made me stop and reconsider. We all have a propensity to ignore the obvious when it doesn’t fit the context within which we live. We turn a blind eye to information when it could cause our world to crumble down around us. This is really the basis of ‘group think.’ We slowly lose the ability to look at our own group objectively. To a degree, breeding elephants is a result of self-preservation. It helps us survive and even thrive within our groups.

My intent in writing this is to expose my own shortcomings—my own humanness, if you will. I want to demonstrate how I ignored signs that I was heading in the wrong direction. I suppressed feelings. I minimized and rationalized away warnings that should have made me stop and reconsider. We all have a propensity to ignore the obvious when it doesn’t fit the context within which we live. We turn a blind eye to information when it could cause our world to crumble down around us. This is really the basis of ‘group think.’ We slowly lose the ability to look at our own group objectively. To a degree, breeding elephants is a result of self-preservation. It helps us survive and even thrive within our groups.

I don’t want people to become critical about everything in life. Life is too short. But I also don’t want people to be afraid to think critically about those things that don’t add up. I want to encourage anyone in any circumstance to not ignore those gut feelings, those signs that cause inner-turmoil. We need to be free to think objectively about ourselves and the groups of which we are a part. It is OK to examine our belief systems, and those of our churches, our leaders, or our organizations.

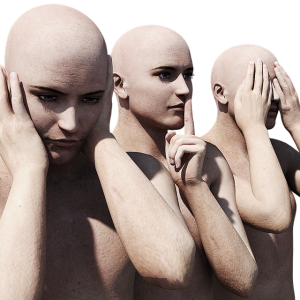

In doing this, there is one thing that I cannot emphasize enough: we can not be afraid to allow objective observers to look at our lives and speak to us about what they see. It is difficult to do. We are prideful, and we know intuitively that they wouldn’t understand if we tried to explain everything about our groups. But we must make the effort to find someone who doesn’t have some ulterior motive of trying to get us to join their group, and who is good at just listening—someone who won’t judge us, but who will be brutally honest with us. Sadly, for many who are involved in groups like the one I was a part of, we don’t feel like we have someone on the outside that we can trust. We have been conditioned to believe that people on the outside have suspect motives or that they are deceived—so they can’t help. But, if at all possible, we all need to find someone who can look at us objectively, which disqualifies those within our groups. I guess what I am trying to say is, we need to ‘open our eyes!’ It is difficult for elephants to breed when our eyes are open and others are watching with us.

At this point, I must point out that I don’t have it all figured out. As a matter of fact, I still have a lot of questions about a lot of issues. But I am not ignoring them, and I’m not afraid to address them. Also, I do not in any way claim to be a scholar or an expert in theology. I just want to share what I do know, and what I have learned. I hope this helps you learn as well.