Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was originally published on March 5, 2015 as part of a series.

Continued from Gissel’s story

I met our friend Shelby Shively while working for the campus newspaper, The Scribe. Shelby was earning a master’s degree in sociology, and she mentioned that the homeschooling population seemed to be understudied in academic literature.

Here is her perspective on Christian fundamentalist, Quiverfull children we were helping to leave their abusive households, in her own words.

I, personally, have come into contact with a handful of homeschooling experiences in my lifetime.

I had three friends who had been homeschooled, two of whom entered semi-public high schools for reasons I do not know.

My friend Mary took a GED test and attempted to take a few online college courses, essentially continuing the homeschool experience as a college student, before realizing she would be better off on an actual college campus. I also had six cousins from my aunt on my father’s side, most of whom she homeschooled.

Mary’s parents were incredibly controlling.

Her older sister used her body for her rebellion: she got her belly button pierced, got haircuts her parents considered strange, and dyed her hair unnatural colors. Mary rebelled in other ways, and she eventually moved out, although she is currently living with her parents again.

My aunt had four boys and adopted a young boy and girl from Russia. She homeschooled her four birth children and the girl she had adopted, but the boy was born with fetal alcohol syndrome. My aunt did not bother to try to understand his learning needs, and rather than alter her own teaching, she sent him to public school.

She was very abusive. She eventually kicked him out, and he tells stories of eating rats at the park when he was homeless. He is now in a transitional program.

I got my bachelor’s degree in sociology and women’s and ethnic studies, and I spent a lot of time learning about domestic violence because I had experienced it from a boyfriend in high school.

It was not until recently that I realized how common my cousin’s story is.

While the details of the situation vary, abuse seems to be common in families that homeschool.

When researching domestic violence and volunteering at a local shelter, I have found very little about children, even adult children, escaping abusive homes and even less about children of homeschool families. One of the only things I have heard is that the majority of homeless teens are escaping abusive homes, though this tells us little about the circumstances surrounding these escapes.

Little academic research has been conducted about abuse in homeschool environments, and the research that has occurred is necessarily incomplete.

Even surveys like the annual survey (part 1 and part 2 and part 3) conducted by the Homeschool Alumni Reaching Out (HARO) group rely on a volunteer sample from the Internet, although it gathers much data that other organizations have not yet attempted to collect and analyzed. Informal surveys are not accessible to people without Internet access, and rely on snowballing (people take it and share it with others from the same population), which tends to yield a more homogenous sample.

Further academic research is needed to determine risk factors for homeschool environments.

Part of the reason so little research has been conducted is because it is simply difficult to properly conduct. Homeschool policies differ based on the state and sometimes even the school district, and record-keeping may also look very different on a state-by-state basis.

It is impossible for a researcher to gather demographics of the homeschool population with inconsistent records or use these records to gather a good, random sample.

Without resources like time and money, a researcher will have difficulty conducting research with homeschool families, especially if these families are reluctant to allow a person to question their motives, tactics, and overall situations.

There are increased difficulties in trying to conduct research with minors; for example, parents who homeschool their children are under no obligation to provide consent for their children to participate in a research project, even if said children would like to participate.

Many, though certainly not all, homeschool families are connected to a church, and the church may be involved in hiding abuse occurring within these families. Many families feel deep paranoia and are not willing to participate in research if they do not perceive the researcher as an ally in some way, such as a member of their church or at least the larger denomination.

The homeschool population is not easy for researchers to access, which is likely one of the primary reasons there is so little research about this population.

It is also possible that researchers lack awareness of the problem. They must be made aware that there is abuse in the homeschool population before they can consider researching it.

My recent awareness of the abuse in the homeschool population has sparked my interest in researching it, but I know there are many struggles to overcome in attempting to reach this population. I also know there are only so many resources available to a person with my current education level, and I may have to set aside this potential research project until I am further educated and perhaps even employed in a university or other research institution.

I can only hope by the time I am fully equipped to conduct this research, others have already done so.

Shelby Shively is a sociology graduate student at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, and former columnist for the student newspaper, The Scribe.

********

Shop at our Amazon store! As an Amazon Influencer, this website earns from qualifying purchases.

Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was

Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was  Mouth shut like a locket

Mouth shut like a locket

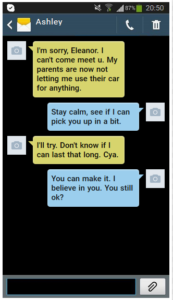

“I’m sorry, Eleanor. I can’t come meet u. My parents are now not letting me use their car for anything.”

“I’m sorry, Eleanor. I can’t come meet u. My parents are now not letting me use their car for anything.”