Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Eleanor Skelton’s blog. It was originally published on December 14, 2015.

I was four years old.

We were visiting my dad’s childhood home in New York, and we went to the house of an elderly lady who used to be his neighbor. She had a caretaker, a single mom homeschooling her son, who was around my age.

My favorite TV show was Barney the Dinosaur, my only 30 minutes of live television once a week. I also played my Barney’s Favorites cassette tape every day and I knew all of the songs by heart.

The little boy and I started chattering and playing on the floor, and I sang “Do Your Ears Hang Low?” for him and his mom, very enthusiastically, with all of the hand motions and marching.

“Do your ears hang low?

Do they wobble to and fro?

Can you tie ’em in a knot?

Can you tie ’em in a bow?

Can you throw ’em o’er your shoulder

Like a continental soldier

Do your ears hang low?”

His mother turned to my mom and said, “Isn’t this why we don’t send them to public school, so they won’t be exposed to garbage like this?”

I remember this deep sense of shame and wanting to crawl under the carpet. I felt like I’d humiliated my mom and I wondered what was so terrible about my song. I think the little boy’s mom called him to come sit on the couch next to her, away from me, and we weren’t allowed to play together the rest of the visit.

This was the first time that I was that child, the bad influence.

Usually it was my parents keeping me away from other children that could lead me astray. This time, they hid their children from me. My mom didn’t understand at all why the other mother objected to the song.

The fear would follow me for years.

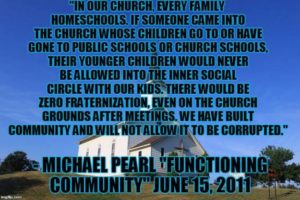

Later on in my teens, we ended up in a church with mostly other homeschooling families, some of them Quiverfull. All the other churches we’d gone to before were mainline denominations, and their children went to public school. But homeschooling was becoming more common by 2004.

I’d hear stories from the other families, pick up things in snatches of conversation.

My sister got a craft book for her eighth birthday party, the only party she ever invited friends to since we stayed to ourselves. The other children said, “Oh, look there’s a witch on this page! We’ll have to cover that up.” Their mom glanced over and said, “Oh yeah, you can just cut out black construction paper and glue it over those pages like we do at our house.”

I called my Bible Buddies partner during the week, we got into a theological discussion, and I asked, “Well, have you ever read Narnia?” “No,” she answered. “My parents don’t like that they talk about magic, and they think it’s too confusing for children to read about Jesus as a lion.” I explained that magic is like a substitute for divine power both in creation and redemption, and I read her some dialogue between Aslan and the Pevensie children. She said she thinks it’s probably safer not to read it and seemed uncomfortable, and I dropped the subject.

A homeschool mom traded some used A Beka textbooks with our family. The pages of the only Greek myth in the 8th grade literature book were stapled together.

“Why should they learn about pagan literature when they could be reading the Bible?”

My dad bought clearance books and films from the Focus on the Family bookstore. He sent the kids Ten Commandments VHS series to a Quiverfull family we knew with 13 kids. My mom explained to their parents that the only time there is music with a beat in the series is the scene where the characters worship false idols.

I was always watchful around the other families, struggling to balance being honest about the books and movies I enjoyed but with the fear of not being allowed to talk to the other teens if I’m considered a “bad influence.” In this patriarchal world, if one of the parents decided I’m not spiritual enough or too worldly, I might not be given space to defend myself.

I know because it happened to others. Teens and young adults were called into the pastor’s office and questioned about their music preferences, asked to stop hanging out with their children.

Because, you know. This is why we don’t send our kids to public school.

********

Shop at our Amazon store! As an Amazon Influencer, this website earns from qualifying purchases.